We, That Now Make Merry in the Room

On Public Libraries, the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, and the Grateful Dead

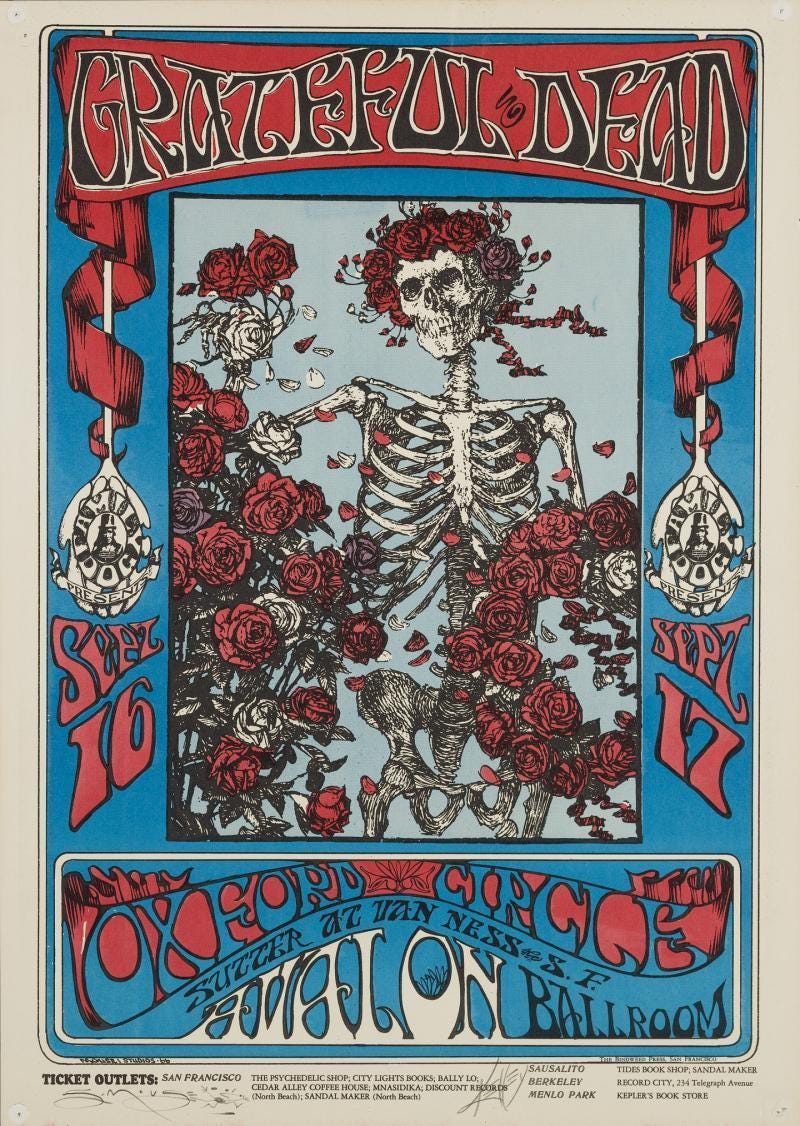

The Grateful Dead’s renowned and adored skull & roses icon — affectionately named Bertha after the song of the same name — was (re)envisioned by Stanley Mouse & Alton Kelley for a 1966 concert at San Francisco’s Avalon Ballroom.

Yet, the work is actually a colored, lysergic version of Edmund J. Sullivan’s illustration for a 1913 edition of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Mouse & Kelley would occasionally head to the San Francisco library in order to garner creative sparks for their work. It is a tale that highlights the use of libraries as eminently fruitful creative spaces, and shows how artists might draw on the public commons in order to better express their work and communities.

The California Historical Society writes on Stanley Mouse, who recalls:

“We would go to the San Francisco library and peruse the books on poster art. They had a back room full of books you couldn’t take out with great references. We were just going through and looking for something. And found this thing and thought, ‘This says Grateful Dead all over it.’”

The Rubáiyát, a Persian gathering of quatrains suffused with tremendous poetic power, was translated by Edward FitzGerald in 1859. Yet, its attribution to Omar Khayyam is debated.

The poetic work greatly influenced the Pre-Raphaelite group of artists, particularly in the Britain. Social and literary clubs dedicated to the Rubáiyát even emerged in the Fin de siècle milieu.

The collision of these seemingly disparate expressive worlds stirred something in me upon discovering this provenance. The free associative countercultural sourcing of a Fin de siècle illustration, found in a Victorian-era translation of a circa 11-13th century work was stunning to me.

It speaks to the timeless and expressive features of the that colored the musical & iconographical palette of the Grateful Dead: from the archetypal, folkloric, and mythological dimensions of lyricist Robert Hunter’s songs, to the visionary cross-pollination of styles, influences, and sounds from a wide historical swathe. The melding of the Rubáiyát with the countercultural design scene reflected this style with tastefulness and intent.

I personally recall growing up with my father introducing me to live Grateful Dead shows, as well as studio work. My very first encounter with both the music and the iconography of the Grateful Dead was incidentally another work by Stanley Mouse & Alton Kelley. In particular, the blue rose depiction which adorns the band’s Closing of Winterland album.

The Dead performed this show on New Year’s Eve at Bill Graham’s Winterland Arena in San Francisco on December 31st, 1978. This peculiar and evocative art flourished into a lifelong adoration for the imagery of the band. The music I heard within also served as an the initial font of inspiration for a budding musician

I later discovered the text of the Rubáiyát just after my undergraduate years, when I discovered a copy held my own public library. I was employed there at the time, and came across it quite casually.

Still, I was intrigued by this uniquely poetic work. It was also during this period that my experience listening to the live recordings of the Grateful Dead deepened.

It felt provedential to have discovered the Rubáiyát in my own similar way within a public library, backgrounded by the context of my experience with the Grateful Dead.

Still, what the experience of both Mouse & Kelley highlights best is the means by which the public commons can serve as an ally to the artist and musician. Libraries, being one of our culture’s most precious assets, are resources beyond expendability.

As such, they supply endless grist for the artistic mill. Inspiration, move us brightly: it is seemingly always built upon the work of those who have created before us. For a moment, consider a world in which open access to these prior works is rendered unavailable or cloistered. In such an instance, inspirational material would be diminished at best, and lost to contemporary artistic spaces at worse.

Long live our libraries!

Bibliography & Sources:

• Image 1: Sullivan, Edmund J. Illustration for he Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. 1913. Sourced from Rolling Stone Magazine, courtesy of the collection of Jacaeber Kastor.

• Image 2: Kelley, Alton & Mouse, Stanley. “Bertha” poster for the Grateful Dead at San Francisco’s Avalon Ballroom. 1966. Via the Denver Art Museum. Rights owned by Rhino.

• Image 3: Kelley, Alton & Mouse, Stanley. Poster for The Closing of Winterland. 1978.

• Passage: Courtesy of the California Historical Society. From an exhibit on the counterculture of the Bay Area.

All of these works are used with here in the respectful spirit of educational & artistic fair use.